Introduction

Contributing to the cultivation of empowerment in schools is one of the various tasks of teaching. As teacher education (TED) contributes to the qualification of future teachers who will be tasked with the cultivation of empowerment, experience with and knowledge about this aspect of teacher work is a crucial part of TED. There is limited research on pre-service teacher students’ participation in their education. The concept of empowerment describes the process by which individuals become able to take control of their living context and circumstances (Adams, 1990, p. 43, as cited in Nikkhah & Redzuan, 2009). According to Westheimer (2022), TED “can prepare teachers to bring meaning and complexity to classroom life and to teach students that they have choices about how we should live and that those choices are the building blocks of democratic engagement” (p. 55). Further, empowerment is also understood as a part of democratic education (Biesta, 2011). Previous research suggests that students’ democratic participation can lead to engagement (Bovill et al., 2016), and that such engagement can lead to empowerment if the teacher educators listen to the students’ voices (Gray et al., 2014), including the critical and aggressive voices (Keddie, 2015). Among various suggestions concerning TED’s opportunities to contribute to the empowerment of future teachers, pre-service teachers’ participation in TED is chosen for investigation in this article.

One of the important preconditions for TED teachers is the ability to foster pre-service teachers’ participation through their involvement in the learning process at all stages. In this article, we use the concept of student democratic participation to describe the space between student engagement and partnership, as well as meaningful collaboration between students and staff (Bovill & Bulley, 2011; Cook-Sather et al., 2014; Masika & Jones, 2016; Zepke, 2015). To do so, student participation is seen in this study as a process rather than an outcome of empowerment.

The concept of participation is often linked to democratic education and education for a democratic community. There is consensus within both national and international (subject-specific) didactics that the cultivation of empowerment must take the form of teaching about, for and through democracy (Arthur & Wright, 2001; Biesta, 2011; Biseth, 2014; Børhaug, 2017; Heldal & Sætra, 2022; Lorentzen & Røthing, 2017; Stray, 2011). In the Norwegian government’s white paper titled Melding. St. 16, Culture for Quality in Higher Education, it is stated that there is a need for a common culture related to quality in education (Meld. St. 16 (2016–2017)). Such a culture of quality will also have to involve cooperation between teachers and students so that students participate in developing study programmes (Meld. St. 16 (2016–2017)). How, then, do Norwegian students in higher education experience participation? In a survey conducted by the Norwegian Agency for Quality Assurance in Education (NOKUT), Norwegian university students were asked: “To what extent do you feel that the students have the opportunity to give input on the content and arrangements of the study programme?” (NOKUT, 2022). The response scale ranged from 1 – To a small extent to 5 – To a large extent. About 40% of the students answered that they experience participation to a large extent (4 or 5), while around 30% answered that they experienced it to a small extent (1 or 2). It is conceivable that the reasons include not only a lack of opportunities for participation but also a lack of information regarding how lecturers follow up on student input.

Contemporary research on participation, empowerment and democratic education is often grounded in the philosophy of John Dewey. Dewey (2007) described democracy as a central value in education and as the practice and purpose of education. Education’s main aim should be to find clarity on the concrete significance of democracy and how to live in a democracy both individually and collectively (Dewey, 2007). All people who are affected by social institutions must have a share in producing and managing them (Dewey, 2007). In this paper, we argue that pre-service teachers are affected by higher education institutions and that they must participate in the production and management of these institutions. Therefore, we investigate how second-year pre-service teachers understand and experience their democratic participation in the planning of seminars in TED.

This article contributes to the call for research on the different ways in which young people become empowered through their democratic participation “in the contexts and practices that make up their everyday lives, in school, college and university, and in society at large” (Biesta, 2011, p. 6). The participants in this study are Norwegian second-year pre-service teachers who participated in the planning of seminar activities during a course titled Pupils’ Academic, Social and Personal Development and Learning in a Diverse Classroom. Student participation in this study is investigated through the following two research questions: (1) How do pre-service teachers understand democratic participation? (2) How do pre-service teachers experience democratic participation?

Conceptual framework

According to Biesta (2006), the role of education is to prepare the next generation for participation in democratic life. In line with Dewey (2007), democracy is primarily understood as a “form of associated living, of conjoint communicated experience” (p. 68). Further, democracy and democratic education are understood by Dewey (2007) as an inherently collective concern that leads to learners’ empowerment. This concept defines the process “by which individuals, groups and/or communities become able to take control of their circumstances and achieve their goals, thereby being able to work towards maximising the quality of their lives” (Adams, 1990, p. 43 as cited in Nikkhah & Redzuan, 2009). Education must provide a good environment for the acquisition of attitudes towards democracy, and the environment must be understood as having conditions that promote or hinder the characteristic activities of a person (Dewey, 2007). Student democratic participation may lead to intellectual development because each individual must decide on various perspectives and solutions provided by other students in the group. Student participation can be an important exercise in democracy (Dewey, 2007), and it is a prerequisite for learning and curiosity. However, democratic participation does not equal free choice of learning activities and topics, because the teacher is responsible for students’ learning outcomes.

There are long traditions in Norway, and other countries, that view schools as key contributors to maintaining and building a democratic society (Børhaug, 2017; Kvam, 2019; Stray, 2011). Even though there exists a consensus in national and international (subject-specific) didactics that education regarding democracy and citizenship should take place in the form of teaching about, for and through democracy, there is no consensus regarding which of the three elements should be emphasised (Biesta, 2011; Biseth, 2014; Stray, 2011; Heldal & Sætra 2022). In the schooling system, there is an inherent asymmetric relationship between the pupil (the child) and the teacher (the adult); participation in school does not equal free choice of learning activities and topics, and the teacher must often initiate, make demands, and sometimes correct the students (Dewey, 2007). Pupils do not have the same full democratic rights in school as they will have in interest organisations, the state, and municipalities as adults, and therefore they should not be led to believe that school is a true democracy even though it has democratic elements (Børhaug, 2017; Kovac, 2018). In the worst case, this may lead to disillusioned future voters and a weakened democracy (Biesta & Lawy, 2006; Solhaug, 2021). In this article, we argue that pupils’ participation in school is dependent on pre-service teachers’ experience of participation in their own TED. Therefore, student teachers must have the opportunity to participate and influence their own TED.

According to Biesta (2006), democratic education consists of three components: (1) the knowledge component (to teach about democracy), (2) the skills component (to contribute to participation and collective decision-making), and (3) the disposition or value component (to support the achievement of a positive attitude towards democracy). These approaches to democracy demand a TED that can educate future teachers to contribute to the development of a democratic society (Zeichner, 2020) and further cultivate the empowerment of school pupils. In other words, in this study, we investigate what pre-service teachers think about democratic participation after they have been through democratic practice, which we, as teacher educators, view as a prerequisite for the qualification of future teachers for democracy.

A culture of participation should be a central and essential component of a democratic society (Biesta, 2011). Additionally, here, students’ understanding of democracy and democratic processes can be increased if they experience participation and mutual decision making (Biesta, 2006). Such participation contributes to the formation of democratic personalities and, therefore, strengthens democracy for future generations (Biesta, 2006). In other words, participation can be an element of democratic education through democracy. This point is relevant to TED, which aims to prepare future teachers who will foster democratic and empowered pupils. Cohen and Uphoff (1980) described participation as people’s involvement in decision-making processes and in the implementation and evaluation of programmes in which they take part. In this regard, participation appears to be a process in which individuals take an active role.

In the last decade, the scope of studies on students’ democratic participation (e. g. how they influence and form their education) has significantly expanded. This has led to diverse concepts that define and illustrate students’ participation. Concepts such as inclusion, participation and engagement refer to students collaborating with teacher educators. From this particular perspective, pre-service teachers are understood as the decision makers, partners, co-designers and co-creators of TED courses, teaching approaches and curricula (Ahmadi, 2021; Bergmark & Westman, 2018). These concepts generally define the space between student engagement and partnership, as well as meaningful collaboration between students and staff. Such collaboration contributes to the development of students’ actual responsibility for the learning process, and students become active agents; at the same time, they develop a meta-cognitive awareness about what is being learned and how (Bovill et al., 2016; Cook-Sather et al., 2014; Magolda, 2006).

According to Cook-Sather (2010), student participation can contribute to the development of students’ responsibility for their learning, and this is possible only when educators position students as actors in education. However, for some students, an opportunity to take responsibility can be experienced as a new role and can lead to uncertainties. These uncertainties can follow from students’ doubts in regard to their responsibility to themselves and others. Indeed, Cook-Sather (2010) argues that educators have to “explicitly – and sometimes repeatedly invite students to participate in decision making and take responsibility” (p. 569). This is even more essential because of the hierarchical nature of society and higher education, wherein decision making in learning and teaching is generally the teacher educators’ domain (Bovill et al., 2016). The research on pre-service teachers’ participation in TED often describes participation in it as a prerequisite for their future profession as teachers. In their study, Bergmark and Westman (2018) shed light on pre-service teachers’ opinions of their experiences of participation in TED as relevant to learning about the professional competencies needed for their future work as teachers. Student participation, however, is not devoid of ambivalence: participation promotes pre-service teachers’ professional development and challenges their willingness to influence decision making. Teacher educators may find student participation uncomfortable (e. g. facing the risk of being criticised) (Bergmark & Westman, 2018; Bovill, 2014; Cook-Sather, 2014). According to Cook-Sather (2014), students’ participation depends on the re-examination of teacher educator and teacher student roles, which can also impact social relationships and hierarchy.

Students’ democratic participation leads to student engagement, which can be described as meaningful participation in, and commitment to, learning (Bovill et al., 2016). According to Gray et al. (2014), students’ active engagement is closely related to students’ voices and empowerment. Over the last three decades, the research on students’ voices has described different ways of engaging students in the educational process. Such research has investigated course evaluations and the co-creation of the curriculum as possible ways to strengthen students’ voices. In line with Keddie (2015), teacher educators should strive to include the voices of all students even when the voices are critical and aggressive.

Given this, our article is based on a study that stresses respect for pre-service teachers’ ability to contribute to the planning of the educational process whereby students appear as joint authors or, more precisely, joint creators of seminars during the semester.

Methods

Study design and data collection

The context of this qualitative study is the second year of Norwegian TED and the focus is on pre-service teachers’ participation in a course called Pupils’ Academic, Social and Personal Development and Learning in a Diverse Classroom. TED in Norway takes place both on campus and in schools. On campus, the educational process is based on theoretical lectures and practical seminars. While lectures can be described as a traditional, teacher-centred approach to promoting learning, the seminars are characterised by a student-centred approach (Emaliana, 2017). Seminars usually provide collaborative learning activities. The main target of seminars is to promote students’ ability to recognise challenging situations in teacher work with diverse classrooms as well as to improve their ability to find solutions to these challenges. In this study, we are investigating two research questions: (1) How do pre-service teachers understand democratic participation? (2) How do pre-service teachers experience democratic participation?

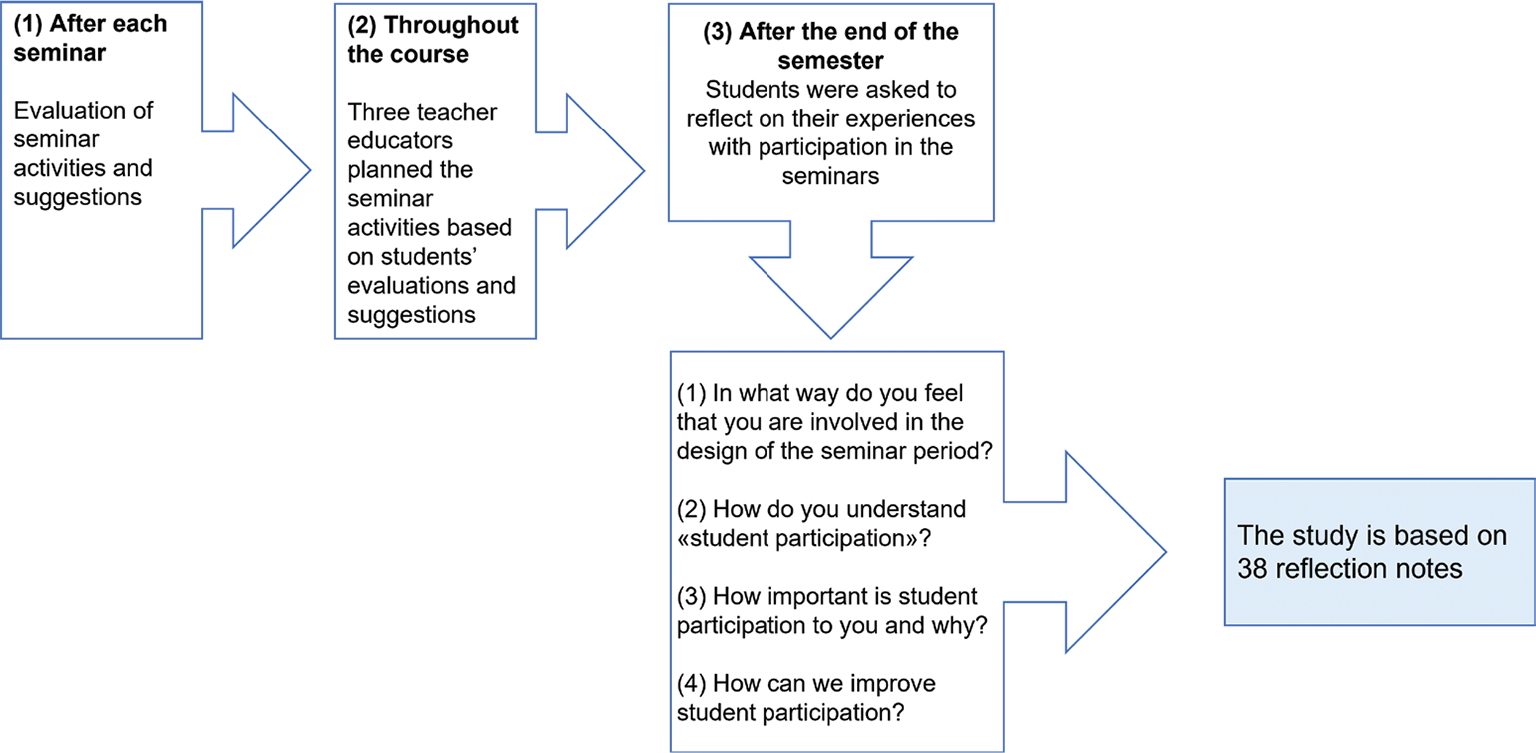

This study examined second year pre-service teachers’ experiences in seminars that utilised different learning approaches such as jigsaw (Anderson & Palmer, 1988), world café (Lorenzetti et al., 2016), think-pair-share (Kaddoura, 2013), and team-based activities (Morris, 2016). Over the course of the semester, the students provided evaluations after each seminar, expressing their interpretations of the approaches used and their preferences for future learning. According to the choice of content, students received opportunities, for example, to suggest specific issues within the thematic content that were already predetermined in the course content. The teacher educators considered the students’ feedback and incorporated it into future seminar planning. At the end of the semester, the students wrote reflection notes responding to the following four questions related to their involvement in seminar design and student democratic participation: (1) “In what way do you feel that you are involved in the design of the seminar period?” (2) “How do you understand student democratic participation?” (3) “How important is student democratic participation to you, and why?” and (4) “How can we strengthen student democratic participation?” A total of 38 anonymous reflection notes were collected. The research design is illustrated in Figure 1.

Data analysis

The data analysis process involved several steps, as outlined in Table 1. The initial step can be described as content analysis, which involved systematising the written data to address the research questions (Postholm, 2010). Categories were identified during this step of data analysis, focusing on pre-service teachers’ reflections on participation and their experiences. The analysis process involved discussions between the researchers and consideration of theoretical grounding and relevant research. The preliminary results were presented to a research group specialising in teachers’ professional development and democracy.

To identify the categories, we made a table in which we systematised all the statements from the pre-service teachers’ reflection notes. During this stage, 12 categories were identified. Among these categories were categories that described students’ experiences of group-based activities, students’ influence on the design of learning activities, and students’ understanding of democratic participation as involvement and an opportunity to give feedback to the teacher educator.

Since the study has two research questions, these 12 categories were sorted into two sections: (1) pre-service teachers’ understanding of participation and (2) pre-service teachers’ experiences of participation. The first section included categories that expressed students’ understanding of democratic participation as co-joining in the planning of seminars, as co-creation and as opportunities for students to express ways of learning that are appropriate for them. The second section included such experiential categories as students’ confidence in teacher educators and the interrelation between pre-service teachers’ initiative and their willingness to participate.

The next stage of analysis aimed to develop characteristic themes within each section. These themes were constructed by combining the identified categories with corresponding quotations. Within the section “Pre-service teachers’ understanding of participation” the theme of participation as an influence on the content of seminars was identified. In the section “Pre-service teachers’ experiences of participation”, the following two themes were identified: (1) participation leads to a feeling of being valuable and (2) participation depends on teacher educators’ initiative and pre-service teachers’ willingness to participate. The process of dataanalysis is illustrated in Table 1.

| 1st step of data analysis:

Content analysis (Examples of quotes) |

2nd step of data analysis:

Identifying of the categories |

3rd step of data analysis:

Dividing the categories into two sections |

4th step of data analysis:

Identifying of themes |

|---|---|---|---|

|

‘For me, participation means that we, the students, can influence how seminars should be’ (37). ‘Students are involved in making seminars as educational and relevant as possible, by influencing the planning of the seminars’ (38). ‘It’s good that the teacher educator gives us the choice to continue with what we did before and what we found to be interesting’ (2). ‘By participating, we can choose the learning activities and topics that we find interesting’ (15). ‘I have been involved in the design of the seminars to a small extent because I am not good at speaking around people, or raising my hand, or expressing my opinion in general’ (36). ‘It is important that we, as pre-service teachers, have the opportunity to facilitate our own learning so that we can get the maximum benefit of the seminar classes and that we have a good learning culture in class’ (1). |

1. Participation as involvement. 2. Participation as providing feedback. 3. Group work, discussions in small groups. 4. Participation as an opportunity to choose something interesting. 5. Influence on the design of learning activities at seminars. |

Section 1: Pre-service teachers’ understanding of participation |

1. Participation as an influence on the content of seminars |

|

‘I have experienced that my teacher educator took our suggestions into account. I feel that I have been heard and my opinion has been appreciated’ (2). ‘I feel that participation allowed us to influence seminars in such a way that we could rather have the activities that we thought were better for learning’ (26). ‘… then we have suggestions about activities in the classroom. I feel that we, the students, also have something important to say about the subjects’ content’ (10). ‘Our teacher educator is good at asking us about what we felt was useful at seminars and how we would like to have our next seminar’ (6). ‘Our teacher educator is always open to all kinds of changes’ (34). ‘This is much easier when the teacher educator takes control, because she has more information about our curricula and our TED’ (12). ‘Pre-service teachers can benefit from doing something they don’t want to do’ (16). |

6. Participation is initiated by the teacher educator. 7. Participation means that the students themselves are willing to provide feedback. 8. Participation and learning environment. 9. Participation as “voting“ 10. Impact of student participation. 11. Teacher educators know best. 12. Conditions that allow for participation. |

Section 2: Pre-service teachers’ experiences of participation |

1. Participation leads to a feeling of being valuable 2. Participation depends on teacher educators’ initiative and pre-service teachers’ willingness to participate |

Validity and reliability of the study

During the analysis, the authors presented the preliminary results to a research group, engaging in discussions and considering alternative interpretations. This validation process contributes to the study’s validity by evaluating different ways to interpret the results before final inferences are made. According to Cook et al. (2002), the concept of validity in qualitative research focuses on the approximate truth of inferences drawn from the data, rather than the data itself. The presentations and discussions of preliminary results with the research group contribute to the validation of the study in the form of an evaluation of alternative ways to interpret the results before presenting the final inference (Creswell & Miller, 2000; Kleven, 2008). In terms of local causality (Miles, 1998, cited by Kleven, 2008), which is an unavoidable dimension of the validation process in qualitative studies, the presented results of this study build on the interpretation of interrelations within data-material and the context of the study. For external validity (Kleven, 2008), the study emphasises the use of thick description, which involves providing detailed descriptions of the context, participants, and study sites (Creswell & Miller, 2000). This approach aims to create authenticity and allow readers to experience or understand the events being described. The context of this study, the data collection procedure, the analysis process, and the results are described in as much detail as possible to contribute to the validity of the study.

Reliability, on the other hand, refers to the trustworthiness and verifiability of the research (Creswell & Miller, 2000). Self-selected participants and individual interpretations of democratic participation and experiences can affect reliability. This study is conducted following the qualitative approach, which is characterised by an awareness that it is not possible to achieve complete neutrality (Patton, 2014). Therefore, it can be expected that other researchers may interpret the data material in another way and make quite different inferences. To keep our interpretations as close to empirical material as possible, we created the categories through an inductive process. At the very first stage of data analysis the categories were given headings from students’ statements to maintain the specifics of the material, and then the categories were further developed into overall themes.

Ethical concerns of the study

The 38 reflection notes were collected anonymously as part of the course evaluation process. The fact that the investigation was introduced by the same teacher educator might contribute to confidence in the research but also could induce reflections that students predict their teacher educator would find appropriate. After the introduction of the study, teacher educators left the room and students filled in the reflection notes alone. Further, since the collection of reflection notes was combined with course evaluations, it might contribute to broader reflections as well as short and superficial answers among those students who do not appreciate the evaluation process. In their reflection notes, students gave their informed consent for the use of their reflections for research purposes. Both the process of analysis and the presentations of the preliminary results to a research group were conducted with respect for the participants and their reflections. The reflection notes used in this investigation are stored following the guidelines of the Norwegian Centre for Research Data (NSD).

Results

How do pre-service teachers understand participation during their TED seminars?

Participation as an influence on the content of seminars

This particular theme explores the outcomes that showcase the comprehension of participation as a significant factor among pre-service teachers. This influence is manifested through the chance to articulate their perspectives on learning activities and collaborate with teacher educators in the formulation of seminar plans. Concerning the impact of students on the selection of suitable activities, the students conveyed that they found the most interesting and attractive activities to be the ones they influenced. They emphasised that their involvement in shaping seminar activities served as a means to express their vision of how these seminars should be conducted. “The participation for me is about the students being able to help to choose how the lessons are to be carried out and making suggestions during the seminar” (4). Students perceive participation as an avenue to affect the inclusion of more appealing activities in seminars. As a result, their active involvement enables them to communicate to their teacher educators the types of learning methods they believe would benefit them the most, according to their own judgment. “For me, participation means that we, students, can influence how seminars should be” (37). Participant 9 describes the opportunity to affect the content of seminars as an unavoidable way of students’ influencing: “Students must participate to make the study as relevant and educational as possible.”

Further, the pre-service teachers expressed that their influence on seminar content and activities also included elements of their appropriate way to learn and often illustrated students’ search for the relevance of campus learning to their future work as teachers. Participants highlight the significant role of student participation in shaping the nature and structure of seminars. By actively engaging in the process, students have the power to influence the direction of the seminars, ensuring that they align with their preferences. “Through participating, students can affect seminars towards the way we, students, wish actually to learn,” describes Participant 12. In addition, Participant 23 expresses: “When I suggest the content of the next seminars, I can affect the learning methods that fit my way to learn.” This statement underscores the influence that students have in determining the learning methods employed during seminars.

By suggesting specific content and activities, students can shape the teaching and learning approaches used, allowing for a more personalised and effective learning experience. It highlights the notion that when students actively participate in the planning process, they can contribute to the selection of learning methods that best cater to their unique learning preferences. Participant 28 expresses that, “Participation is important because it is precisely us students who have to learn this new material.” Students underscore the significance of active involvement in the learning process. This emphasises that students themselves are the primary beneficiaries of the educational experience and, therefore, their participation is crucial. By actively engaging in seminars and taking part in the planning and execution of activities, students take ownership of their learning journey. This quote highlights the understanding that students are not passive recipients of knowledge but active participants in constructing their own understanding. By being actively involved in seminars, students can shape the learning environment to suit their needs and enhance their learning outcomes. This participant thus recognises that students play a vital role in their own education and emphasises the value of their active engagement in acquiring new knowledge and skills.

When it comes to the content of seminars, it is recognised as a collaborative endeavour involving both students and teacher educators. This mutual activity entails a close partnership, as they work together to plan and bring seminars to life. The students themselves have described this collaborative process using phrases like “taking part in,” “working together with the teacher educators,” and “assisting the teacher educators.” They play an active role in shaping the seminars.

A key aspect highlighted by the students is the opportunity to have a say in selecting the activities that are incorporated into the seminars. This element of choice empowers them and instils a sense of ownership over the content being covered. By having a voice in determining the direction of the seminars, students develop a stronger connection to the subject matter and a greater motivation to learn. This involvement in the decision-making process contributes significantly to their engagement and overall educational experience.

How do pre-service teachers experience participation during their TED seminars?

Participation leads to a feeling of being valued

The participants involved in the seminars expressed that their active participation led to a profound sense of value and importance. By providing suggestions and actively contributing to the planning and implementation of seminar activities, the pre-service teachers felt that their voices were acknowledged and respected by the teacher educators. This recognition and validation of their input enhanced their overall experience. Participant 25 notes that, “The opportunity to influence the seminars makes it more interesting and fun to attend seminars.”

Moreover, the feeling of being seen and heard was further reinforced when the teacher educators incorporated the students’ suggestions into the formation of the seminars. The fact that their ideas were not only acknowledged but also implemented demonstrated a genuine willingness on the part of the teacher educators to value the perspectives and contributions of the pre-service teachers. This strengthened the sense of being seen, heard, and valued within the learning environment.

By creating a collaborative space where student input was actively sought and utilised, the seminars fostered a sense of empowerment and meaningful engagement for the pre-service teachers. It affirmed their belief in their own capabilities and reinforced their motivation to actively participate in the learning process. “I have experienced that my teacher educator took our suggestions into account. I feel that I have been heard and my opinion has been appreciated” (2).

Because the pre-service teachers could suggest feasible activities during the semester, in their experience, through this response, they became capable of changing something in the course that they did not find conducive to their own learning. “I feel that participation allowed us to affect seminars in such a way that we could rather have the activities that we thought were better for learning” (26).

The opportunity to enact change contributed to their experience of having an opportunity to make suggestions, as well as to make changes in their own learning situation. “Then we have suggestions about activities in the classroom. I feel that we, students, also have something important to say about the subjects’ content” (10).

Some pre-service teachers described increased motivation to attend and actively participate in seminars. The motivation described here suggests that these students are connected to a feeling of ownership of the subject and the content of the seminars.

Participation depends on teacher educators’ initiative and pre-service teachers’ willingness to participate

This theme is built on interrelated preconditions that pre-service teachers experience as essential for their participation. Based on the experiences of the pre-service teachers in this study, participation is possible only when teacher educators take the initiative and create a space in which to convey their opinions and suggest changes or improvements to seminars. “Our teacher educator is good at asking us about what we felt was useful at seminars and how we would like to have our next seminar” (6). Participant 34 describes the teacher educator as follows: “Our teacher educator is always open to all kinds of changes” (34).

The pre-service teachers experienced opportunities to participate when the teacher educators asked them what they were interested in learning within the given learning outcomes and themes, as well as what kind of seminar activities they preferred for enhancing their own learning process. At the same time, student participation is possible only when pre-service teachers themselves are willing to give their responses to activities during seminars. Additionally, in turn, pre-service teachers’ willingness to participate depends on the teacher educators’ willingness to take students’ suggestions into account in the planning of seminars.

However, three of the pre-service teachers who participated in this study believed that their teacher educators knew best regarding what pre-service teachers needed to do and to learn to become qualified teachers. Participant 12 describes this in the following quote: “This is much easier when the teacher educator takes control because she has more information about our curricula and our TED” (12). One of these pre-service teachers mentioned that pre-service teachers probably learned more from the activities suggested by teacher educators (which they may have initially disliked) than from the activities that the students suggested themselves. This insight is emphasised by the following quote: “Pre-service teachers can benefit from doing something they don’t want to do” (16).

Discussion

This study investigated two research questions: (1) How do pre-service teachers understand democratic participation? (2) How do pre-service teachers experience democratic participation?

The second-year pre-service teachers describe their understanding of democratic participation as an influence that allows them to impact the content and form of seminars. Our study suggests participation depends on the following preconditions: teacher educators initiate the opportunity to influence the education, pre-service teachers take part in influencing it and teacher educators take into account students’ suggestions in the planning of seminars. Together, these preconditions contribute to pre-service teachers’ exercise of democracy (Dewey, 2007), which is important for TED teachers as those who can cultivate empowerment in their future classrooms. Participation has been described as an active process, and individuals who participate have been described as active (Cohen & Uphoff, 1980). The experience of taking an active part in the planning of seminars and being treated seriously can strengthen pre-service teachers’ understanding of democratic participation. In turn, this can further contribute to their experience of democratic participation, which is necessary for their development and qualification as teachers who can contribute to the development of democratic society through teaching pupils (Zeichner, 2020).

When the students described their understanding of participation as an influence, they demonstrated an awareness of the ways of learning most appropriate for them, which further illustrates that students are responsible for their own learning. This responsibility comes into play in pre-service teachers’ suggestions regarding seminar activities. Perhaps their understanding of participation also reflects that they think like teachers and thus use the opportunity to participate in the design of seminars as if they were teachers themselves. In our study, we did not find that pre-service teachers directly linked their experiences of participation to their future profession as teachers as described in previous studies (e.g. Bergmark & Westman, 2018). The students expressed their perspectives on learning while describing the learning activities from which they and their co-students benefitted the most. Nonetheless, the experience of making suggestions and being heard could strengthen students’ ability to have control over their own life and circumstances, which contributes to the empowerment of pre-service teachers.

It should not be forgotten that three of the pre-service teachers who participated in this study expressed confidence in teacher educators’ knowledge and experience in qualifying future teachers. This confidence can be interpreted as pre-service teachers’ trust in teacher educators’ professionalism, but it may also illustrate that pre-service teachers are uncomfortable taking responsibility for their own learning (Bergmark & Westman, 2018; Bovill, 2014; Cook-Sather, 2014). This result may seem interesting given the hierarchical system, which assumes, among other things, that those who teach the students have knowledge and experience of how students learn, and which methods are most relevant to pre-service teachers. This claim, however, is challenged by the widespread idea that learners are experts in their own learning and should speak up to influence the learning environment to their advantage. Here, there is perhaps no conclusion, and variation and balance are most desirable in TED.

Dewey (2007) describes democracy as a conjoint communicated experience. The results of our study also show that democratic participation is impossible without communication between both pre-service teachers and teacher educators. The students’ understanding of participation reflects that it is a reciprocal and mutual process. Teacher educators must facilitate participation by inviting students to convey their suggestions and opinions. At the same time, the pre-service teachers themselves must accept the invitation and make use of this opportunity.

Seminars constitute one of several types of learning activities in TED. In other words, seminars are part of pre-service teachers’ circumstances. As the results of our study illustrate, in pre-service teachers’ experience, their participation leads to a feeling of being valuable and being able to make a change in their circumstances. In line with Adams (1990, as cited in Nikkhah & Redzuan, 2009), the concept of empowerment describes the process by which individuals receive the opportunity to take control of their surroundings. According to this description of empowerment, collecting pre-service teachers’ suggestions for seminar activities can be understood as a process of empowerment. Pre-service teachers describe feeling valuable and heard whilst also feeling capable of making changes to those activities that concern their everyday lives. This can constitute one of the outcomes of the empowerment process.

Because the expectations of TED’s influence on the qualification of future teachers are increased, it is even more important to contribute to the pre-service teachers’ exercising of democracy through participation. In line with Biesta (2006), participation should be seen as the process of pre-service teachers’ continuing involvement in different stages of TED. Further, TED should develop a conducive environment for such participation whereby teacher educators create space and opportunities for pre-service teachers’ involvement while remaining aware that students may experience discomfort in taking responsibility for their own learning during seminars. One possible way to create such learning environments could be a collaborative interplay between teacher educators and pre-service teachers, wherein the latter appear as joint authors and co-enquirers of learning activities (Fielding, 2011, 2012). The collection of pre-service teachers’ evaluations and suggestions after each seminar for further planning of the next seminars during the semester is an example of such an interplay.

Biesta (2006) explained that participation contributes to the formation of democratic personalities and therefore strengthens democracy for future generations. Unfortunately, the process of participation described in this study was limited to one semester of pedagogy in TED. This limits the impact it may have had on pre-service teachers’ attitudes towards democracy, but the study demonstrates that participation holds great potential if democratic involvement is taken into account by teacher educators. It further demonstrates that democratic participation can lead to pre-service teachers feeling capable and valuable, which are important elements of learning about democracy and their future profession. If TED aims to succeed in the qualification of future teachers for democratic life, the participation of pre-service teachers should be common practice during education, not merely relegated to short, sporadic events during regular TED course evaluations.

Conclusion

This study explored Norwegian second-year pre-service teachers’ understanding and experiences of participation in TED. To conclude, we find it crucial to be aware of pre-service teachers’ understanding of participation as an influence that gives them the opportunity to impact seminar activities and to change them into more appropriate ways to learn. The experience of the pre-service teachers in this study was that their participation in the planning of seminar activities contributed to empowerment, which has been described as being able to change students’ everyday circumstances. In addition, the students noted that participation depends on teacher educators’ initiative and pre-service teachers’ willingness to participate in decision making. Still, the student who suggested that students may benefit more from the very activities they initially dislike makes a valuable point in terms of how learning also takes place in processes that are uncomfortable and unpredictable (Brookfield, 2017). Our study also indicates some advantages that follow student democratic participation, whereby a re-examination of the roles of teacher educator and student is necessary for cultivating empowerment in TED.

References

- Ahmadi, R. (2021). Student voice, culture, and teacher power in curriculum co-design within higher education: An action-based research study. International Journal for Academic Development, 28(2), 177–89. https://doi.org/10.1080/1360144X.2021.1923502

- Anderson, F. J., & Palmer, J. (1988). The jigsaw approach: Students motivating students. Education, 109(1).

- Bergmark, U., & Westman, S. (2018). Student participation within teacher education: Emphasising democratic values, engagement and learning for a future profession. Higher Education Research & Development, 37(7), 1352–1365. https://doi.org/10.1080/07294360.2018.1484708

- Biesta, G. J. J. (2006). Beyond learning: Democratic education for a human future. Paradigm.

- Biesta, G. J. J. (2011). The ignorant citizen: Mouffe, Rancière, and the subject of democratic education. Studies in Philosophy and Education, 30, 141–153. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11217-011-9220-4

- Biesta, G. J. J. & Lawy, R. (2006). From teaching citizenship to learning democracy: Overcoming individualism in research, policy and practice. Cambridge Journal of Education, 36(1), 63–79. https://doi.org/10.1080/03057640500490981

- Børhaug, K. (2008). Politisk oppseding i norsk skule [Political upbringing in the Norwegian school]. Norsk Pedagogisk Tidsskrift, 92(4), 262–274. https://doi.org/10.18261/ISSN1504-2987-2008-04-03

- Børhaug, K. (2017). Ei endra medborgaroppseding? [A new upbringing for citizenship?] Acta Didactica Norge, 11(3). https://doi.org/10.5617/adno.4709

- Bovill, C. (2014). An investigation of co-created curricula within higher education in the UK, Ireland and the USA. Innovations in Education and Teaching International, 51(1), 15–25. https://doi.org/10.1080/14703297.2013.770264

- Bovill, C., Cook-Sather, A., Felten, P., Millard, L., & Moore-Cherry, N. (2016). Addressing potential challenges in co-creating learning and teaching: Overcoming resistance, navigating institutional norms and ensuring inclusivity in student–staff partnerships. Higher Education, 71(2), 195–208. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10734-015-9896-4

- Brookfield, S. (2017). Becoming a critically reflective teacher. Josey‐Bass.

- Cohen, J. M. & Uphoff, N. T. (1980). Participation’s place in rural development: Seeking clarity through specificity. World Development, 8(3), 213–235. https://doi.org/10.1016/0305-750X(80)90011-X

- Cook, T. D., Campbell, D. T., & Shadish, W. (2002). Experimental and quasi-experimental designs for generalized causal inference. Houghton Mifflin.

- Cook-Sather, A. (2010). Students as learners and teachers: Taking responsibility, transforming education, and redefining accountability. Curriculum Inquiry, 40(4), 555–575. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-873X.2010.00501.x

- Cook-Sather, A., Bovill, C., & Felten, P. (2014). Engaging students as partners in learning and teaching: A guide for faculty. John Wiley & Sons.

- Creswell, J. W. & Miller, D. L. (2000). Determining validity in qualitative inquiry. Theory into Practice, 39(3), 124–130. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15430421tip3903_2

- Dewey, J. (2007). Democracy and education: An introduction to the philosophy of education. NuVision.

- Emaliana, I. (2017). Teacher-centered or student-centered learning approach to promote learning? Jurnal Sosial Humaniora, 10(2), 59–70. https://doi.org/10.12962/j24433527.v10i2.2161

- Gray, C., Swain, J., & Rodway-Dyer, S. (2014). Student voice and engagement: Connecting through partnership. Tertiary Education and Management, 20, 57–71. https://doi.org/10.1080/13583883.2013.878852

- Heldal, J., & Sætra, E. (2022). Demokratisk medborgerskap som tverrfaglig tema og formål i skolen [Democratic citizenship as an interdisciplinary topic and objective in school]. In H. F. Nilsen (Red.), Myndig medborgerskap. Demokrati i lærerutdanningen (p. 61–72). Universitetsforlaget.

- Huang, L., Ødegård, G., Hegna, K., Svagård, V., Helland, T., & Seland, I. (2017). Unge medborgere: Demokratiforståelse, kunnskap og engasjement blant 9.-klassinger i Norge [Young citizens: Understanding democracy, knowledge and involvement among Norwegian ninth-graders] (NOVA rapport 15/17). https://oda.oslomet.no/oda-xmlui/handle/20.500.12199/3470

- Kaddoura, M. (2013). Think pair share: A teaching learning strategy to enhance students’ critical thinking. Educational Research Quarterly, 36(4), 3–24.

- Keddie, A. (2015). Student voice and teacher accountability: Possibilities and problematics. Pedagogy, Culture & Society, 23(2), 225–244. https://doi.org/10.1080/14681366.2014.977806

- Kleven, T. A. (2008). Validity and validation in qualitative and quantitative research. Nordic Studies in Education, 28(3), 219–233. https://doi.org/10.18261/ISSN1891-5949-2008-03-05

- Kovac, V. B. (2018). “Schooling through democracy”: Limitations and possibilities. Education, 139(1), 1–14. https://www.ingentaconnect.com/content/prin/ed/2018/00000139/00000001/art00001

- Kvam, V. (2019). Jakten på den gode skole [Searching for the good school]. Universitetsforlaget.

- Lorenzetti, L. A., Azulai, A. & Walsh, C. A. (2016). Addressing power in conversation: Enhancing the transformative learning capacities of the World Café. Journal of Transformative Education, 14(3), 200–219. https://doi.org/10.1177/1541344616634889

- Magolda, M. B. B. (2006). Intellectual development in the college years. Change: The Magazine of Higher Learning, 38(3), 50–54. https://doi.org/10.3200/CHNG.38.3.50-54

- Meld. St. 16 (2016–2017). Kultur for kvalitet i høyere utdanning [Culture for quality in higher education]. Ministry of Education. https://www.regjeringen.no/en/dokumenter/meld.-st.-16-20162017/id2536007/

- Morris, E.J. (2016). Academic integrity: A teaching and learning approach. In T. Bretag, (Ed.), Handbook of academic integrity. Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-287-098-8_11

- Nikkhah, H. & Redzuan, M. R. (2009). Participation as a medium of empowerment in community development. European Journal of Social Sciences, 11(1), 170–176.

- NOKUT. (2022). Rapport: Studiebarometeret 2021 – Hovedtendenser Studiebarometeret 2021 [Report: The student survey 2021]. https://www.nokut.no/globalassets/studiebarometeret/2022/hoyere-utdanning/studiebarometeret-2021_hovedtendenser_1-2022.pdf

- Patton, M. Q. (2014). Qualitative research and evaluation methods: Integrating theory and practice. Sage Publications.

- Solhaug, T. (2021). Skolen i demokratiet – demokratiet i skolen [School in democracy – democracy in school]. Universitetsforlaget.

- Stray, J. H. (2011). Demokrati på timeplanen [Democracy on the agenda]. Fagbokforlaget.

- Westheimer, J. (2022). Can teacher education save democracy? Teachers College Record, 124(3), 42–60. https://doi.org/10.1177/01614681221086773

- Zeichner, K. (2020). Preparing teachers as democratic professionals. Action in Teacher Education, 42(1), 38–48. https://doi.org/10.1080/01626620.2019.1700847