Introduction

An important part of work in different professions consists of relational communication practice, expressed through language, voice, body, gaze and face. An important part of teachers’ work thus constitutes being seen, heard and understood in communicative practice in encounters with pupils, colleagues and parents. This performative relational communication practice is a cross-disciplinary competence, which, independent of subject, is of great importance for the performance of pedagogical practice. This competence is what we in this position paper refer to as Professional Orality (PO). In a position paper1 a potential field of knowledge is envisioned, or an urgent theme in need of exploration is described (Tarr, 2008). Hence, a position paper is not based on one specific empirical study. Still, this position paper has a background in long standing learning in a landscape of practice (Wenger-Trayner & Wenger-Trayner, 2015) connected to education and teaching of oral communication. In this position paper we form a statement regarding the characteristics of professional orality. The position paper also presents a basic arts educational model suggested for the training of professional oral skills. By focusing on professional orality as a central field of competence in the practice of teachers, teacher educators and other professionals, we wish to increase the awareness of the importance of oral expression as a highly specialised skill in the domain of the teaching profession, and thereby contribute to knowledge development and improved competence within the profession. We describe the need for, and make an argument for, the importance of this competence in the basic education of all phonic professions, where the practitioner is dependent on a well-functioning voice. In this paper, however, we focus on the teaching profession.

Statement

In this position paper we will make an argument for the need to define the contours of a research field for professional orality, PO. We also position ourselves through outlining a basic arts educational model for training of PO. So far, we have found support for the argument from voice physiology, logopedics, rhetoric, drama, storytelling and orality studies. The main point in our argumentation is that professional orality represents a theme, not only as orality to communicate something, but to communicate precisely and trustworthily in oral form. Our point of departure in this paper is to make visible the need for research on the performative competence of oral interpretation and practice in the teaching profession. It is the orality itself that is focused on in our research, the means of expression in orality, as well as the impact of oral expression forms. The argumentation for professional oral skills as a research field rests upon Ong’s (1982) work suggesting orality to be phenomenologically and culturally different from written language/literacy. We also draw support from research carried out by Haugsted (1999, 1998). He maintains that orality in teaching is something different from teaching orality. Furthermore, we are inspired by Høegh’s (2008) research exposing how body, senses and intuition serve as an immediate oral interpretation in encounters with poetry, which she calls a ‘poetic pedagogy’.

In this position paper, we suggest professional orality (PO) to be a specialised competence within a teacher’s practice, with skills that can be described, trained and assessed. The analytic question for the exploration in this paper is: How can the characteristics of professional orality as a field of knowledge in teacher education be described and expressed in an arts educational model for training of professional oral skills?

Structure of the article

We first present the state of the art in relevant research areas. After that, we outline three perspectives through which we explore the potential research field, PO. The first perspective is an ethical one connected to the profession, where the issues under scrutiny are credibility, responsibility and integrity. The second perspective is an epistemological one: What knowledge is at stake in PO, and how do skills develop through teaching and learning? We suggest a performative aesthetic approach in PO, developing through practice. We focus on a basic arts educational model aimed at the training of professional oral skills in teacher education. The third perspective we outline in this article regards learning as transformative learning in PO. We address critique directed at this field of knowledge and conclude with the main points in the argumentation acknowledging professional orality as a field of knowledge in teacher education.

State of the art – a selected literature review

This section of the paper comprises a selected review of research and development work carried out in relevant fields of research. Based on a search of databases, we have selected 10 dissertations, 11 articles, 16 books/book chapters and two master theses for our review. The focus on the topic orality for the review was initially planned to be orality in teacher education. However, we found interesting studies also from other professions which we wanted to include. The review is restricted to three perspectives: (1) professional communication, especially oral communication, (2) studies of voice disorders in professions, and (3) relational competence and self-focus. We are looking for what perspectives are already covered, and what perspectives we can develop within the chosen field of knowledge. We have a special focus on studies from Finland, because the field of oral communication has for a long period had a place in teacher education and been a subject of research there.

In the following review of research, we find interesting studies within rhetoric research, logopedic research about teachers’ voice disorders, and many other fields. Of special interest are studies focusing on the potential of training professional oral communication. Studies of artistic communication in storytelling and the performance of poetry will not be described, even though we acknowledge their importance for the theme.

Studies of professional communication

An important part of the work of many professional practitioners is to be seen, heard and understood in a relational oral communication practice. The importance of trustworthiness and credibility in professional communication is well documented. Despite this, international research (e.g. Gray 2010, p.40) shows that many newlyeducated professionals enter their career with inadequate oral communication skills. Gray suggests that the umbrella term ‘oral communication’ needs to be concretised to investigate how students experience the benefits of specific oral skills. An American survey (CSAS, Communication Skills Attitude Scale) mapping attitudes towards the training of professional orality among medical students (Rees, Sheard & Davies, 2002) has also been adapted for use in several languages in the education of other professions. A lack of sufficient oral expression skills has been discovered within different professions.2 The professional performance of oral skills as an assembled personal competence seems to be a scarcely-explored field of research.

In rhetoric research the part of a presentation called Actio, the oral presentation, has been studied by Gelang (2008) and Kindeberg (2015). Hvass (2003) has also written explicitly about oral communication from a rhetoric perspective, to aid readability, mainly focusing on voice and breathing. Kindeberg (2006) has described a pedagogic rhetoric focusing on trustworthiness. She suggests that the interpretative, forming and expressive skills can be concretised and discussed. To create trustworthiness, according to Gelang, there is a need for knowledge regarding both verbal and bodily expression. She describes developing an Actio capital according to four elements: face, gaze, voice and gestures (Gelang, 2008).

Finland has a long tradition of working with oral communication as an individual course (5 study points) in teacher education, and even as a minor subject (25 study points) (Furu 2011, 2017; Østern, 1987,1989). Pupils in upper secondary school can take a diploma in oral communication based on 2–10 courses in oral communication (Valkonen, 2012; Østern, 1994). At the Faculty of Humanities at the University of Jyväskylä there has been, since the mid-1980s, a department of speech communication. The name of the department was changed to the Department of Language and Communication Studies in 2017. Its profile is described in the following way:

The research in Speech Communication has a long tradition at the University of Jyväskylä. Over the years, the program has become one of the most significant European centers of internationally recognized research in the field. Our research focuses on the core area of dynamics of human interaction in working life.3

At the department there is scientific competence through a professorate in communication science, and a considerable number of doctoral dissertations have been produced during the period 1986–2018. We will now turn to a few Finnish studies within the field of oral communication from the doctoral dissertations of university lecturers in speech communication. Three dissertations from different contexts expose the multitude of approaches when focusing on oral communication. The three contexts are teachers and students in a university of applied sciences (called polytechnics), medical students learning about how to meet patients, and a study regarding communication in Finnish education and school culture.

Kostiainen (2003) carried out research on the teaching of communication in Finnish polytechnics through interviews with 28 teachers and 64 students, plus a survey of graduates. She found that their view of the importance of communication did not change over time as their working life developed. An implication of her study is that the teaching of communication is connected to professional image and identity – and not solely to specific communication practices and situations. Koponen (2012) tried out different ways to work with the communicative skills of medical students in encounters with patients, through role play and forum theatre. The medical students reported positive benefits from all forms of training regarding their preparation for meeting and understanding communication with patients. Olkkonen’s (2013) study maps restrictions and opportunities in communication in Finnish education and school culture. Her point of departure is artistic work within the teaching of oral communication and voice use. In her study pedagogy, teaching and learning, as well as artistic work, are woven together in education. One of Olkkonen’s findings is that work with voice as a knowledge field of its own has the potential to support the development of a moral subject.

A study by Furu (2011), a teacher of logopedics and voice, comprises research on the development of teacher students’ own voices into a functioning and professional working tool. Her study is the second one at the Faculty of Education at Åbo Akademi University that explores the students’ voices as a pedagogical resource. In 1987 A. L. Østern carried out a study where teacher students’ own evaluation of voice qualities (the prosodic elements) was compared with the self-evaluation of the teacher. Both A.-L. Østern and Furu later published textbooks in oral communication for teacher education (Furu 2017; Østern, 1989). Furu (2011) finds there is a need for contemplation time for students to make them aware of their own voice.

Studies of voice disorders in professions

There is extensive evidence in research showing that teachers are in a profession at risk of developing voice disorders. In a quantitative study by Willard (2007) regarding teachers and use of voice, 80% of the research informants considered it demanding to use their voice in teaching. There is a large amount of research connected to the professional use of voice and, more generally, about communication.4

The human voice as an instrument is built into the body, a fact that makes it influenced by both physical and mental circumstances. Teachers as professional voice users are in a profession at risk, in terms of their voice wearing out and regarding symptoms of voice fatigue (Urbach, 2008; Vilkman, 2007). Until 1980, song and voice use was a subject in Norwegian teacher education, and parts of the necessary competence in oral skills were addressed in teacher education (Årva, 1987). Compared with, for instance, Finnish teacher education (Furu, 2011), the absence of systematic training of the teacher voice is noteworthy in current Norwegian, Danish and Swedish teacher education.

Studies of relational competence and self-focus

The necessity of self-focus to develop relational skills has received support in recent neurological research (Getz, Kirkengen & Ulvestad, 2011; Singer, 2017). Both Singer and Bolz (2018) and Singer and Engert (2019) have published neuroscience-based research, where they conclude that the training of relational and emotional skills is of importance for the participants’ physical and mental health.

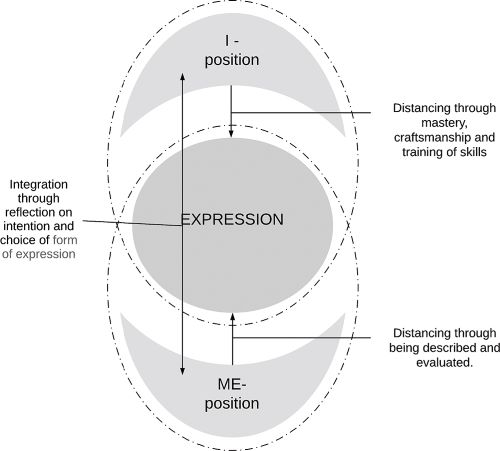

Of special relevance for our research project is Schøien’s (2011) study, based on her work with the training of student priests’ oral communication in the context of worship. In detailed analyses she shows (a) the importance of focused training, (b) that it is possible to train these skills, and (c) that the learning process is transformative. Schøien finds expression for a necessary focusing on oneself in her analysis of student priests’ experiences of preparation and carrying out their first liturgy and sermon. The study articulates a challenge related to the simultaneity of the orality: at the same time as the expression is formed, it influences the listener. This connection between creating an expression and being influenced by it gives the performer a double role in the artistic process. Schøien describes the teacher’s work as helping the students to alternate between intentional and expressing work, between closeness and distance to their own expression, encountering different levels of consciousness. In Figure 1 Schøien indicates how work with professional oral expression can progress with space for self-reflexivity and for the development of artistic precision in communication and presentation. This model of an arts educational approach (Schøien 2011, pp. 36–39; 249–253, translated from Norwegian), is inspired by a study by Halvorsen (2005), and exposes the systematic exchange between closeness and distance in the artistic work Halvorsen has her focus on (Halvorsen, 2007, pp. 139–143).

The model in Figure 1 shows how the student builds a necessary distance to his or her own oral expression by evolving mastery and craftmanship in the expressive I-position, and through descriptive feedback in the observing me-position.

Of interest also is research within the Danish Relational Competence Project (2012–2016) in teacher education at VIA University College, Aarhus. The project explores practice focused on the relational, embodied and sensuous in teaching.5

Research on quality in teaching shows the importance of the teacher for the pupils’ learning (Danielsen, 2018, Drugli 2012; Krane, Karlsson, Ness & Kim 2016; Timperley, Wilson, Barrar & Fung, 2007). However, this research has primary focus on teaching methods and learning theories in the practice of pedagogy, and not on the competence connected to the practitioner. Danielsen (2018) proposes an alternative plan for tutoring students in oral communication, based on Ong’s (1982) central work about orality and literacy as different cultures related to different phenomena.

Furuseth (2003) explored language and voice and found that sight and listening work differently. While the gaze can be analytical and distancing, listening is different. It demands that the listener takes in what is heard, which means that the listener will be vulnerable through the corporeal fusion with what is sensed and incorporated. Stavik-Karlsen (2013) argues for the teacher being a person with authenticity, presence and vulnerability, as opposed to what he calls a ‘distanced learning officer’. Stavik-Karlsen suggests that the strength of a trustworthy teaching practice emanates from the courage needed to be vulnerable. Biesta (2014) maintains that real education always involves a risk. When applied to the training of professional oral skills it implies enduring others directing their attention at you, something that presupposes a healthy self-image, according to Øiestad (2009).

Rønnestad and Skovholt (2003) explored professional development in a longitudinal study of counsellors and psychotherapists. They found that when the discrepancy between what a person wants to appear as and what the person experiences becomes too great, there is a real danger that the practitioner will stagnate in a non-purposeful and rigid performance called premature closure or leave the profession (Rønnestad, 2008; Rønnestad & Skovholt, 2003).

Summing up the state of the art

Through this restricted review of research and development work within the chosen fields of oral communication, voice disorders, and relational competence and self-focus, we find a considerable interest in exploring aspects of oral communication. Researchers have acknowledged the importance of professional communication skills. Research has also uncovered the risks of voice fatigue and the experiences of voice problems among teachers and other professionals. The importance of self-focus in training oral as well as relational skills has also been put on the philosophical and research agenda. Where our research project fits in is connected to professional orality, where the phenomenon itself is focused on, and where the ethical integrity of the professional practitioner/teacher is of great importance. In the following section we address issues connected to ethical awareness, such as credibility, responsibility and integrity, in the training of professional oral skills.

Ethical argumentation as a perspective in PO

Teacher education has, like all profession education, the aim to qualify to practice a concrete vocation. Professions can be described as independent, knowledge-based vocations with special privileges and obligations. A criterion for a profession is precisely the high degree of personal commitment of each professional practitioner – this is also a moral obligation. Biesta (2015) in the article How Does a Competent Teacher Become a Good Teacher? claims that competence alone is not enough. The ability to make wise choices based on ethical awareness regarding the most fundamental teacher task is, according to Biesta, a necessary skill based on a virtue-based approach to the practice of teaching.

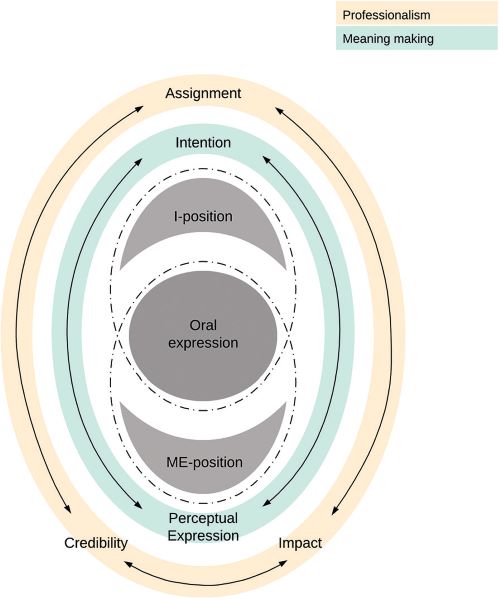

The model in Figure 1 exposes the possible gap between a teacher’s intention on the one hand and another person’s understanding on the other. In Figure 2 the I- position and me-position in the expressive work process is reframed according to the professional assignment and duty of teaching.

Firstly, the blue ellipse describes how the intention of a teacher’s expression is in connection with what another person perceives as the meaning (the perceptible expression). The intention and the perceived meaning might be quite far away from each other. Secondly, Schøien’s model (the brown elliptic form) outlines how the assignment is dependent on the credibility of the teacher, and thus also the impact the performance of the assignment might have. This shows the teacher’s oral expression as a professional duty.

Research on the training of PO (Schøien, 2013, 2016) indicates that although the intention relates to the professional assignment, credibility is first and foremost connected with the perceived understanding of the oral expression, exposed in voice, face, eye contact, body and gestures.

Research shows that teachers’ ethical work is often unconscious, reactive, not according to any plan, and that teacher students are not prepared for this work during their teacher education (Cooke, 2017). Cooke’s argument for focusing on the teacher as a moral person is that pupils will be affected by the teacher’s appearance, behaviour, attitudes and disposition, and that teachers cannot withdraw from the ethical responsibility to the relational aspect in teaching. Both Cooke and Biesta have a virtue-based ethical approach, and emphasize that the teacher is a human being with virtues and values, which form the way he or she appears in the practice of the profession. Cooke asks: ‘The question remains for future educators of teachers: how to develop moral character and virtues in novice and experienced teachers so they are able to enact virtue in their teaching?’ (Cooke, 2017, p.2). This moral character is necessary, not least because the profession has an extended degree of autonomy in its practice.

An education for a profession provides knowledge and skills, but also basic attitudes. The education guarantees that both the autonomous and expert assessment choices the practitioner makes are in correspondence with the values and ethical standards of the profession. The binding and ethical code also guarantees to those who receive the service that the practitioner will serve with integrity according to the ethical standards and, if necessary, putting his or her own needs aside (Grimen, 2008, p. 72). Medical doctors have their own doctoral vow, originally the Hippocratic oath (500 years BC)6, and for teachers in Norway Professional ethics for the teaching profession (2014)7 is a basic document which is binding for the practice of the profession. Likewise, teacher students in Norway and in Finland who do not fulfill the professional standards or suitability criteria (2005)8 can be denied entrance into the profession, even if they have a command of the necessary subject knowledge of the profession.

The general part of the framework curriculum in Norway, The Promotion of Knowledge9 (Core Curriculum and the Quality Framework, 2006, p. 22), writes about the teacher in the following way:

The most important tool teachers have is themselves. For this reason, they must dare to acknowledge their own personality and character, and to stand forth as robust and mature adults in relation to young people who are in a process of emotional and social development. Because teachers are among the adult persons children interact most closely with, they must venture to project themselves clearly, alert and assured in relation to the knowledge, skills and values to be transmitted.

When teaching professional oral skills, these ethical issues can be explored. It is an ontological question how a person is in the world and becomes anew with the world. We see the potential of creating a site-specific ontology for a professional community (cf. Schatzki, 2002) like a school or a teacher education, based on credibility, responsibility and integrity expressed in professional oral communication.

In professions where the practitioner encounters other people, presence, authenticity in communication and relation are decisive for the establishment of confidence, to convey and receive necessary knowledge and to show respect. Concepts like autonomous and responsible professional practitioners with an ethically-obligated integrity can be found in the aims of education. However, there is little done to concretise in what form this communicative, relational presence will become visible in the professional practice.

In the next section we present a view of knowledge, adopting a performative and aesthetic approach in teaching and learning, and the ways in which we plan to train participants and study the impact of a course in professional orality.

Performative and aesthetic approach to teaching and learning in a transdisciplinary context

The basis for the professional practice that teacher education provides not only demands competence in planning and evaluating pedagogical activities. This foundation also qualifies teachers for the performance of these activities in real life. The focus on practice makes the teacher a role model and visible as a person, grounded in the tasks of the profession: influencing, educating, teaching and supervising the pupils. An important methodological choice is to externalise knowledge, making tacit and implicit practical knowledge explicit by giving verbal expression to descriptions and evaluations. All subjects taught in basic education demand performative skills, which we assume subject teachers try to provide within the frame of their teaching. By gathering descriptions of all the performative skills the students need and articulating what is common, competence in expression that is overarching for all subjects will become visible as PO. As a performative part of the profession this knowledge field stands out as a profession subject but not as a subject discipline. Here, the relation between different fields of knowledge plays together, and therefore we call PO a field of knowledge.

PO is, however, based on an extended concept of knowledge (Grimen, 2008; Zenhua, 2008) which embraces practice knowledge (Janik, 1996; Molander 1996), tacit knowledge (Johannessen, 2004; Polanyi, 2000) and explicit knowledge. This might challenge the understanding of learning, mentoring and assessment forms in the teacher education field. A cross-disciplinary cooperation allows for different scientific positions among the participants. The form of cross-disciplinarity we work with is closer to transdisciplinarity in the way it is described by Nicolescu (2010) as beyond disciplines. E. Wenger-Trayner and B.Wenger-Trayner (2015) use the concept knowledgeability to mark how a person embodies knowledge in practice. They suggest this term to relate to

… the complex relationships people establish with respect to a landscape of practice, which make them recognizable as reliable sources of information or legitimate providers of services. Like competence, knowledgeability is not merely an individual characteristic. (p. 23)

They further suggest that knowledgeability is a complex achievement, combining many relationships of identification and dis-identification through multiple modes. They describe these relationships as fragments of experience to be assembled in moments of engagement in practice. (p.24)

We call PO a pre-subject competence, because what bundles the field of knowledge together is the real competence the practice of the profession demands, which is what lies before the educational program itself. Different parts of the professional practice are tied to different knowledge forms and learning methods, and these can be found in a specific subject.

Transdisciplinarity includes both academic and non-academic disciplines and is connected to an alternative epistemology. In Charter of Transdisciplinarity (CIRET 1994) Article four, a basic understanding of transdisciplinarity is described in the following way: ‘… the semantic and practical unification of the meanings that traverse and lay (sic) beyond different disciplines’. It is, thus, both a foundation and a reality that everyone must cope with, something overarching. From this description of different forms of knowledge bundled together in a transdisciplinarity, we move to a more hands-on description of how teaching and learning works within PO. We turn to performative and aesthetic approaches in the social sciences. Here, Gergen and Gergen (2018) are our references for a performative turn in social sciences.

The performative teacher and researcher of PO

Gergen and Gergen (2018) write about a performative movement in social sciences, where the researchers ask questions like: What is the research good for? How can it contribute to a positive change for the group I study? A performative researcher does not take an objective stance but is quite clear about the values the research builds on. The performative researcher starts in practice. Haseman (2006) wrote a manifesto for performative research where he announced that practice takes the lead. As researchers with a performative approach, we wish to stage a practice – the training of PO, and from the practice generate research and research findings. As performative researchers, we use arts-based methods in our inquiry into the field of PO.

With inspiration from Appelbaum (1995) and Fels and Belliveau (2008, p. 36), we have a special focus on stop moments in the training process. The notion of the stop moment in the research methodology of performative inquiry is used as a site for action. A stop is ‘… a moment of risk, a moment of opportunity that calls us to attention … it provides a way to focus on the learning that emerges …’ .

In the training of PO, one such stop moment might be the moment when a person realises that the oral expression is not understood in the way the person intended. The awakening awareness is a stop moment, making learning possible. With a performative approach, the learner tries out in practice different ways of presenting him or herself through oral expressions and gets iterative opportunities to explore nuances of interpretations when he or she is experimenting with oral expressions, by training oral artistic precision. A.-L. Østern and Hovde (2019, p. 172) write:

Through stop moments we come to see things, events, or relationships from new perspectives. These moments call for awareness of the possible choices of action and the consequences of our actions. These moments occur in interstices, betweenness, in gaps between opening and closing. These moments have a lot of energy and potential, as they can give us direction.

The aesthetic approach as sensuous and embodied

A performative approach is an aesthetic approach, emanating from theatre and performance theory (Schechner, 2013). What is characteristic of a performative approach is that you present, as an event, for the first time, and you do not repeat, but find a way to present anew in new events. This is also very much what characterises orality, according to Ong (1982): the need to be present if something is presented.

Dale (1989) uses the concept of narcissistic surplus about the energy needed to make oneself an object for emotional interest, reflection and evaluation of others (Dale 1989, p.76, our translation). Dale is engaged in what he calls aesthetics in the ways colleagues communicate in teaching situations:

We also see that the communication, the self-presentation among colleagues, contains aesthetic qualities. /…/ If we develop skills in what I argue for, we can direct attention especially on the interplay between gestures, bodily attitudes, voice tone, expressions of feelings, mime, and we can interpret the meaning of them, in different situations, on different stages. Aesthetics as style is an expression given form, expressiveness staged, scenic performances. (Dale, 1989, p. 75, our translation from Norwegian)

Here, Dale describes an important aesthetic performer competence within pedagogical professionality. To concretise a standard for self-presentation practice is a first step towards being able to assess or make demands regarding oral relational expression skills within a profession.

The bodily turn in research (cf. Anttila, 2013; Sheets-Johnstone, 2009) has opened for understanding the importance of an aesthetic approach to teaching and learning, recognising bodily affects and sensations as important in learning. Aesthetic, in the sense of being a thinking-feeling person in encounters with materials, nature and culture, is crucial for depth in learning (Tochon, 2010; T.P. Østern & Dahl, 2019).

The performance of the professional practitioner’s oral skills seems to be a scarcely explored and described field. In the next section we address how the training of PO in principle can be carried out.

How professional orality can be trained as part of teacher education – a developed basic arts educational model

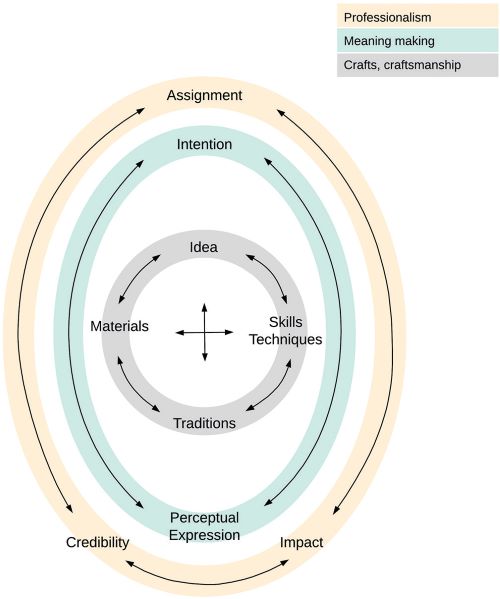

Training of PO creates a necessary space where attention is on the practitioner’s self-presentation and personal oral expression (Furu, 2011; Schøien, 2011). Whilst Figure 2 takes the process of alternating between two different positions as a starting point for understanding the developing of professional oral expression competence, Figure 3 takes the model a step further by including the crafts of orality.

In the third version of the model a small grey circle is placed in the middle, indicating the crafts of orality. Oral precision and clarity (the blue elliptic form) and ethical obligation in the teacher’s professional practice (the brown elliptic form) are completed with a grey circle, which describes the crafts of orality. The craft of art in general consists of knowledge as well as testing out materials and techniques, thus developing skills and artistic precision. The art forms have much in common, but they are separated by the materials, skills and traditions they have. Within many art forms the final expression is not dependent any more on the artist’s presence. The specific challenge for orality as an expression, simultaneous in time and place, is that the distance between the expression and the person expressing is non-existent.

To make different types of art expressions one needs to develop different skills and use different materials. In the development part of the planned research project we try out the basic arts educational model for development of teacher identity through interpretative work with oral expression practice. A methodological innovation in this project is the performative, aesthetic approach emanating from practice, and focusing on stop moments as learning moments, which we connect to a meta-perspective on the transformative development of the professional practitioner.

The third perspective we introduce in this paper is a learning perspective relevant for PO. The perspective is based on Mezirow’s transformative learning theory and further developments.

Adults’ experiential transformative learning – being pushed towards the edge of one’s personal comfort zone

How adults learn is illuminated with Mezirow’s (2000) transformative learning theory. In the Nordic countries, Illeris (2013) has elaborated the theory and connects transformative learning to identity as professional practitioner. Adult learners can become more knowledgeable, more insightful, less prejudiced, more reflective and emotionally open for change. Mezirow (2006) suggests two basic learning forms: instrumental learning that gives answers to the question of how something is performed, and communicative learning that gives answers to the question why and can be connected to understanding of arrangements in the surrounding world based on norms and values.

Mezirow (2000) described four degrees of potential transformation in the adult in a learning process: adjusting the existing frames of reference; exchanging the frames with new ones; relocating oneself to make new meaning perspectives visible; and learning new habits of mind. The adult has already, in earlier formative phases, acquired understandings and convictions, which do not easily change. New frames of reference may perhaps provoke resistance, both cognitively, emotionally and socially. The learner must therefore see the benefit/usefulness and purpose with the new frames of reference and habits of mind.

Taylor and Jarecke (2009, p. 282–284) sum up what different authors in Transformative Learning in Practice have brought to the forefront as important in adults’ learning. They write, ‘… learners are most susceptible to new learning when they are on the edge of their comfort zones – their learning edge’.

Illeris (2013, p. 26–28) refers to Taylor and Jarecke in an interpretation of some principles representative of transformative learning processes. Illeris mentions as the first principle that the learning should be meaningful and explorative. Your starting point is something familiar, but the goal is to end up with something qualitatively new. Another principle that Illeris describes is to confront power positions and to involve oneself in differences. A third principle is fantasy and imagination. Emotional experiences, creativity and emotional engagement play an important role in learning. Furthermore, Illeris mentions the exploration of boundaries and articulates (2013, p. 27, our translation) the following when a participant runs into their own limits: ‘Many examples show that uneven sequences with obstacles, breaches, problems and challenges promote emotional intensity and innovative thinking and thus promote transformative learning’.

The principle that transformative learning implies reflection is central, but Illeris points out that this reflection must imply self-reflection and critical reflection to contribute to transformative learning. Finally, Illeris mentions that one should not underestimate the model function in the inspiration the participants get from the teacher as a person; as a model they want to resemble.

We have now introduced three perspectives of importance for training and for the study of professional oral skills. In the next section we take a critical stance in approaching some attitudes towards the training of professional orals skills, and we ask why PO is so scarcely focused on and prioritised in basic teacher education.

Critical remarks concerning a talent-based understanding of skill

General voice qualities, oral communicative skills and professional oral skills as a field of competence might lack concrete criteria for a description of competent practice. This makes both learning and assessment difficult in basic teacher education. This might partly be due to a talent-based understanding of skill (Schøien, 2011, 2013), dependent on ability from birth – skills that only to a minor extent can be learnt. This is partly because of a kind of naive thinking, suggesting that ‘all can talk’, that makes training unnecessary. Another explanation might be that what it is possible to say something about with authority is dependent on what is made accessible for systematic thinking – through languaging. This indicates that the field needs to encounter re-learning and a re-focusing of attention. Here, the issue concerning knowledgeability might become a theme when approaching the vulnerable teacher/student person. What is ascribed to be of importance in professional teacher education does not necessarily connect to an understanding of what is central or not for functioning practice but connects to what the profession owns in terms of language to discuss, concepts to handle, and criteria for assessment. In the concluding part of this position article we repeat our statement and acknowledge the main perspectives of importance for research in PO.

Conclusion

In the description of the state of art we have identified a certain interest in parts of the knowledge field, PO. We have found studies relevant to PO within a broad spectrum of disciplines. We have also found, as an answer to our analytical question, that what is not yet strongly focused on is a specific professional focus on orality, grounded in an ethical awareness and obligation regarding credibility, responsibility and integrity, defined as a cross-disciplinary, transdisciplinary field of knowledge. We have also, as one part of the answer to the analytical question in this paper, presented a basic arts educational model for training of PO in Figure 3. The lack of a collected knowledge base makes the knowledge field also lack the weight of a subject milieu and a demarcation of the field of knowledge that it might contribute to.

In this position paper, we have articulated the need for research that (1) explicitly contributes to the identification of which specific skills are important in what we describe as professional orality; (2) maps which forms of knowledge are at stake and which resources from different existing subject fields it is appropriate to use; (3) develops concrete teaching modules, where learning aims, progression, knowledge contribution and educational thinking are challenged and can be motivated, and (4) explores what the training of professional oral skills and the development of a profession-specific oral expression competence can contribute regarding the professional practitioner’s self-understanding and integration of professional identity as a teacher.

Finally, we suggest that there is a need for research on a transdisciplinary basis:

*Acknowledging that oral utterances are not writing, have other means of expression and interpret and communicate with sensuous-embodied, intuitive and performative means and modes;

*Acknowledging professional orality as a special field of research;

*Acknowledging oral precision and clarity as an ethical obligation in relational professional practice;

*Acknowledging orality as simultaneous in both time and (mostly) place, as an immediate expression of credibility, responsibility and integrity.

References

- Anttila, E. (2013). Koko koulu tanssii! Kehollisen oppimisen mahdollisuuksia kouluyhteisössä [The whole school is dancing! The possibilities in bodily learning in school context]. Acta Scenica. Helsinki: University of the arts. Retrieved 1.9.2019 from http://actascenica.teak.fi/eeva-anttila-2013/

- Biesta, G. J. J. (2014). The beautiful risk of education. Boulder, Colorado: Paradigm.

- Biesta, G. J. J. (2015). How does a competent teacher become a good teacher? On judgement, wisdom and virtuosity in teaching and teacher education. In R. Heilbronn & L. Foreman-Peck (Eds.), Philosophical perspectives on the future of teacher education (pp. 3–22). Oxford: Wiley Blackwell.

- CIRET (1994/ 2012). Charter of Transdisciplinarity. Retrieved from http://basarab-nicolescu.fr

- Cooke, S. (2017). The moral work of teaching: A virtue-ethics approach to teacher education. In D. J. Clandinin & J. Husu (Eds.) The SAGE handbook of research on teacher education (pp. 419–434). Los Angeles: Sage.

- Dale, E. L. (1989). Pedagogisk profesjonalitet. Om pedagogikkens identitet og anvendelse. Oslo: Gyldendal.

- Danielsen, Ø. (2018). Munnleg språk – ein undringsplan: Refleksjonar over Walter J. Ong og framlegg til ein undervisningsplan i munnleg kommunikasjonar i norskfaget. In M. H. Hoveid, H. Hoveid, K. P. Longva & Ø. Danielsen (2018). Undervisning som veiledning (pp. 159–189). Oslo: Cappelen Damm.

- Drugli, M. B. (2012). Relasjonen lærer og elev - avgjørende for elevenes læring og trivsel. Oslo: Cappelen Damm.

- Fossli-Jensen, B. (2011). Hospital doctors` communication skills - A randomized controlled trial investigation of the effect of a short course and the usefulness of a patient questionnaire. (Diss.) Oslo: UiO, Faculty of Medicine.

- Furu, A-K. (2011). En resa i röstens landskap. En narrativ studie av hur lärare blir professionella röstanvändare. (Diss.). Åbo: Åbo Akademis Förlag.

- Furu, A.-K. (2017). Professionell röstanvändning i läraryrket. Stockholm: Studentlitteratur.

- Furuseth, S. (2003). Mellom stemme og skrift. Oslo: Universitetet i Oslo. (Diss.). Institutt for nordistikk og litteraturvitenskap, NTNU, Trondheim. https://core.ac.uk/download/pdf/52101329.pdf

- Gelang, M. (2008). Actiokapitalet – retorikens ickeverbala resurser. Åstorp: Retorikförlaget

- Gergen, K. J. & Gergen, M. (2018). The performative movement in social science. In P. Leavy (Ed.), Handbook of arts-based research (pp. 54–67). New York: Guilford.

- Getz, L., Kirkengen, A. L., & Ulvestad, E. (2011). Menneskets biologi – mettet med erfaring. Tidsskrift for den norske legeforening, 7(131), 683–687.

- Grimen, H. (2008). Profesjon og kunnskap. In A. Molander & L. I. Terum (Eds.), Profesjonsstudier (pp. 71–86). Oslo: Universitetsforlaget.

- Gray, F. E. (2010). Specific oral communication skills desired in new accountancy graduates. Business Communication Quarterly, 73(1), 40–67. Article first published online: January 28, 2010; Issue published: March 1, 2010

- Halvorsen, E. M. (2005). Forskning gjennom skapende arbeid? Et fenomenologiskhermeneutisk utgangspunkt for en drøfting av kunstfaglig FoU-arbeid. HiT-skrift 5. Porsgrunn: Høgskolen i Telemark. Retrieved from http://teora.hit.no/dspace/handle/2282/153

- Halvorsen, E. M. (2007). Kunstfaglig og pedgogisk FoU. Nærhet, distanse, dokumentasjon. Kristiansand: Høyskoleforlaget.

- Haugsted, M. T. (1999). Handlende muntlighet: mundtlig metode og æstetiske læreprocesser. København: Danmarks lærerhøjskole.

- Haugsted, M. T. (1998). Handlende muntlighet. (Diss.). Danmarks lærerhøyskole, København.

- Hvass, H. (2003). Retorik – at lære muntlig formidling. København: Hans Reitzels Forlag.

- Høegh, T. (2008/2009). Poetisk pædagogik. Sprogrytme og mundtlig fremførelse som litterær fortolkning. Forslag til ny tekstteori og til pædagogisk refleksion. (Diss.). Institut for Nordiske Studier og Sprogvidenskab, Det Humanistiske Fakultet, Københavns universitet, København.

- Illeris, K. (2013). Transformativ læring & identitet. Frederiksberg: Samfundslitteratur.

- Ihmeideh, F. M., Al-Omari, A. A., & Al-Dababneh, K. A. (2010). Attitudes toward communication skills among student-teachers in Jordanian public universities. Australian Journal of Teacher Education, 35(4). http://dx.doi.org/10.14221/ajte.2010v35n4.1

- Janik, A. (1996). Kunskapsbegreppet i praktisk filosofi. Stockholm: Brutus Östlings Bokförlag Symposion.

- Johannessen, K. S. (2004). Praksis, kunnskapssyn og analogisk tenkning. Et alternativt fundament for forståelse av læring. SkY Skrift, 1, 75–97.

- Kindeberg, T. (2006). Pedagogisk retorik: En skiss till den muntliga relationens vetenskap. Exemplet högskoleläraren. Rhetorica Scandinavica, nr 38, pp. 45–61.

- Kindeberg, T. (2015). Tilltro som grundläggande vilkor för förebildligheten som pedagogiskt stöd. Rhetorica Scandinavica, nr. 70 pp. 72–89.

- Kostiainen, E. (2003). Viestintä ammattiosaamisen ulottovuutena [Communication as a dimension of vocational competence] (Diss.). Jyväskylä: University of Jyväskylä.

- Koponen, J. (2012). Kokemukselliset oppimismenetelmät lääketieteen opiskelijoiden vuorovaikutuskoulutuksessa [Experiental learning methods in the training of medical students’ communication skills] (Diss.). Tampere: University of Tampere.

- Krane, V., Karlsson, B. E; Ness, O. & Kim, H. S. (2016). Teacher–student relationship, student mental health, and dropout from upper secondary school: A literature review. Scandinavian Psychologist 3:e11

- Laurence, B., Bertera, E. M, Feimster, T., Hollander R. & Stroman, C. (2012) Adaptation of the communication skills attitude scale (CSAS) to dental students. Journal of Dental Education, 76, (12), pp. 1629–1638.

- Mezirow, J. (2000). Learning to think like an adult: Core concepts of transformation theory. In J. Mezirow & Ass., Transformative Learning. Learning as transformation: Critical perspectives on a theory in progress (pp. 3–34). San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

- Mezirow, J. (2009). Transformative learning theory. I J. Mezirow & E. Taylor (Eds.), Transformative learning in practice: Insights from community, workplace, and higher education (pp. 18–32). San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

- Molander, B. (1996). Kunskap i handling. Göteborg: Daidalos.

- Nicolescu, B. (2010). Methodology of transdisciplinarity – levels of reality, logic of the included middle and complexity. Transdisciplinary Journal of Engineering & Science. 1 (1), 19–38.

- Ong, W. J. (1982). Orality and literacy: technologizing of the word (2nd ed. 2000). New York: Routledge.

- Olkkonen, S. (2013). Äänenkäytön erityisyys pedagogiikan ja taiteellisen toiminnan haasteena [The speciality of voice uses as a challenge in pedagogy and artistic work]. (Diss.). Helsinki: University of the Arts.

- Polanyi, M. (2000). Den tause dimensjonen. En introduksjon til taus kunnskap Oslo: Spartacus forlag.

- Rees, C. Sheard, C. & Davies, S. (2002). The development of a scale to measure medical students’ attitudes towards communication skills learning: The Communication Skills Attitude Scale (CSAS). Medical Education, 36, 141–147.

- Rønnestad, M. H. (2008). Profesjonell utvikling. In A. Molander & L. I. Terum (Eds.), Profesjonsstudier (pp.280–294). Oslo: Universitetsforlaget.

- Rønnestad, M. H. & Skovholt, T. M. (2003). The journey of the counselor and therapist: Research findings and perspectives on professional development. Journal of Career Development, 30, 5–44.

- Schatzki, T. R. (2002). The site of the social: A philosophical account of the constitution of social life and change. University Park: Pennsylvania State University Press.

- Schechner, R. (2013). Introduction to performance studies. (3rd edition edited by S. Brady). New York: Routledge.

- Schøien, K. S. (2011). Hvordan øve hellige handlinger. En profesjonsdidaktisk studie av treningen av muntlige ferdigheter i en norsk presteutdanning. (Diss.) Åbo: Åbo Akademi Press.

- Schøien, K. S. (2013). Det muntliges kunst. In Østern, A-L, Stavik-Karlsen, G. & Angelo, E. (Eds.) Kunstpedagogikk og kunnskapsutvikling (pp. 83–95). Oslo: Universitetsforlaget.

- Schøien, K. S. (2016) Perspektiver på en veiledningspraksis med drastiske og paradoksale trekk. «Utfordrende, ubehagelig, utmattende og … nødvendig». In A.-L. Østern & G. Engvik (Eds.) Veiledningspraksiser i bevegelse. Skole, utdanning og kulturliv (pp.159–180). Bergen: Fagbokforlaget.

- Schøien, K. S. (2017). The oral professionality of teachers: Methodological questions. Paper presentation at the International Rhetorical Education Conference in Gothenburg, October 2017.

- Sheets-Johnstone, M. (2009). The corporeal turn: An interdisciplinary reader. Exeter, UK: Imprint Academic.

- Singer, T. & Bolz, M. (2018). Compassion: Bridging practice and science. http://www.compassion-training.org

- Singer, T., & Engert, V. (2019). It matters what you practice: Differential training effects on subjective experience, behavior, brain and body in the ReSource Project. Current Opinion in Psychology, 28, 151–158. DOI: 10.1016/j.copsyc.2018.12.005.

- Stavik-Karlsen, G. (2014). Konturer av sårbarhetens pedagogikk. In A-L. Østern, G. Stavik-Karlsen & E. Angelo (Eds.), Dramaturgi i didaktisk kontekst (pp. 149–168). Bergen: Fagbokforlaget.

- Tarr, P. (2008). New visions: Art for early childhood a response to art: Essential for early learning. A position paper by the Early Childhood Art Educators Issues Group (ECAE), Art Education, 61:4, 19–24, DOI: 10.1080/00043125.2008.11652064

- Taylor, E. W. & Jarecke, J. (2009). Looking forward by looking back. I J. Mezirow & E. Taylor (Eds.) Transformative learning in practice: Insights from community, workplace, and higher education (pp. 275–290). San Fransisco: Jossey-Bass.

- Timperley, H. S., Wilson, A., Barrar, H., & Fung, I. (2007). Teacher professional learning and development: Best evidence synthesis. Wellington: Ministry of Education.

- Tochon, F. V. (2010). Deep education. Journal for Educators, Teachers and Trainers, 1, 1–12.

- Urbach, A. K. M. (2008): Stemmetretthet blant lærere. En kartleggingsstudie. Retrieved from https://www.duo.uio.no/bitstream/handle/10852/32047/MasreroppgavenxtilxAnnexKatrinexMoexUrbach.pdf

- Valkonen, T. (2003). Puheviestintätaitojen arviointi: näkökulmia lukiolaisten esiintymis- ja ryhmätaitoihin [Assessing speech communication skills: Perspectives on presentation and group communication skills among upper secondary school students]. (Diss.). Jyväskylä: University of Jyväskylä.

- Vassdal, K. (2017). Når stemmen svikter - en kvalitativ studie av presters stemmevansker. (Master thesis). Bodø: Nord universitet.

- Vilkman, E. (2000) Voice problems at work: A challenge for occupational safety and health arrangement, Folia Phoniatrica et Logopedica: Jan-Jun 2000; 52 (1–3), 120–125.

- Wenger-Trayner, E. & Wenger-Trayner, B. (2018). Learning in a landscape of practice: A framework. In E. Wenger-Trayner, M. Fenton-O’Creevy, S. Hutchinson, C. Kubiak & B. Wenger-Trayner, Learning in landscapes of practice: Boundaries, identity, and knowledgeability in practice-based learning (pp. 13–29). London and New York: Routledge.

- Zhenhua, Y. (2006). On the tacit dimension of human knowledge. Bergen: University of Bergen

- Øiestad, G. (2009). Selvfølelsen. Oslo: Gyldendal.

- Østern, A.-L. (1987). Rösten som arbetsredskap. Vasa: Pedagogiska fakulteten vid Åbo Akademi. Studie nr 25.

- Østern, A.-L. (1989). Tal- och uttryckspedagogik. Helsinki: Finn Lectura.

- Østern, A.-L., Granfors, U., Malmström, K. & Snickars-von Wright, B. (1994). Muntlig kommunikationsfärdighet i årskurs sex och årskurs nio. Slutrapport över uppdragsforskning för Utbildningsstyrelsen. In A.-L. Østern (Ed.), Evaluering i modersmålet – nordiskt perspektiv (pp.1–115). Publikation nr 13. Vasa: Pedagogiska fakulteten vid Åbo Akademi.

- Østern, A.-L. & Knudsen, K. N. (Eds.) (2019). Performative approaches in arts education: Artful teaching, learning and research. Routledge Research Series. London and New York: Routledge.

- Østern, T. P. & Dahl, T. (2019). Dybde//læring – med overflate og dybde. In T. P. Østern, T. Dahl, A. Strømme, J. Å. Petersen, A.-L. Østern & S. Selander, Dybde//læring – en flerfaglig, relasjonell og skapende tilnærming (pp. 39–56). Oslo: Universitetsforlaget.

- Årva, Ø. (1987). Musikkfaget i norsk lærerutdannelse 1815–1965: et skolefags utvikling og skjebne gjennom 150 år. Oslo: Novus.

Fotnoter

- 1. A typical position paper is a short feature that presents a newsworthy issue, introduces and outlines a specific position, validates and identifies the consequences of such a position, identifies significant knowledge gaps or presents hypotheses within an actual field. (Cf. the journal Educare https://ojs.mau.se/index.php/educare/about/submissions#position)

- 2. The research examples, for instance, concern hospital doctors (Fossli-Jensen, 2011), accountants (Gray, 2010), teachers (Ihmeideh, Al-Omari & Al-Dababneh, 2010), dentists (Laurence, Bertera, Feimster, Hollander & Stroman, 2012) and priests (Schøien, 2011, 2016).

- 3. https://www.jyu.fi/hytk/fi/laitokset/kivi/en/ourdepartment/disciplines/communication/research

- 4. A Norwegian overview in Norsk tidsskrift for logopedi 2/2016.

- 5. http://www.bornslivskundskab.dk/forskning Parts of the relational competence project are now continued in an EU-funded project «HandinHand»( www.handinhand.si)

- 6. https://sml.snl.no/hippokratiske_ed

- 7. https://www.utdanningsforbundet.no/globalassets/larerhverdagen/profesjonsetikk/larerprof_etiske_plattform_a4_engelsk_311012_051015argh.pdf

- 8. https://lovdata.no/dokument/LTI/forskrift/2005-10-10-1193

- 9. https://www.udir.no/globalassets/filer/lareplan/generell-del/core_curriculum_english.pdf